| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

A stereotype defines how an existing metaclass may be extended, and enables the use of platform or domain specific terminology

or notation in place of or in addition to the ones used for the extended metaclass.

Description

Stereotype is a kind of Class that extends Classes through Extensions.

Just like a class, a stereotype may have properties, which may be referred to as tag definitions. When a stereotype is applied

to a model element, the values of the properties may be referred to as tagged values.

Generalizations

•

“Class? on page 116

Attributes

No additional attributes

Associations

• icon : Image [*] Stereotype can change the graphical appearance of the extended model element by using attached icons. When

this association is not null, it references the location of the icon content to be displayed within diagrams presenting the

extended model elements.

Constraints

[1] A Stereotype may only generalize or specialize another Stereotype.

generalization.general->forAll(e |e.oclIsKindOf(Stereotype)) andgeneralization.specific->forAll(e | e.oclIsKindOf(Stereotype))

[2] Stereotype names should not clash with keyword names for the extended model element.

Semantics

A stereotype is a limited kind of metaclass that cannot be used by itself, but must always be used in conjunction with one

of the metaclasses it extends. Each stereotype may extend one or more classes through extensions as part of a profile. Similarly,

a class may be extended by one or more stereotypes.

An instance “S? of Stereotype is a kind of (meta) class. Relating it to a metaclass “C? from the reference metamodel (typically

UML) using an “Extension? (which is a specific kind of association), signifies that model elements of type C

can be extended by an instance of “S? (see example Figure 13.12). At the model level (such as in Figure 13.17) instances

of “S? are related to “C? model elements (instances of “C?) by links (occurrences of the association/extension from “S’ to

“C?).

Any model element from the reference metamodel (any UML model element) can be extended by a stereotype. For example in UML,

States, Transitions, Activities, Use cases, Components, Attributes, Dependencies, etc. can all be extended with stereotypes.

Notation

A Stereotype uses the same notation as a Class, with the addition that the keyword «stereotype» is shown before or above the

name of the Class.

When a stereotype is applied to a model element (an instance of a stereotype is linked to an instance of a metaclass), the

name of the stereotype is shown within a pair of guillemets above or before the name of the model element. If multiple stereotypes

are applied, the names of the applied stereotypes are shown as a comma-separated list with a pair of guillemets. When the

extended model element has a keyword, then the stereotype name will be displayed close to the keyword, within separate guillemets

(example: «interface» «Clock»).

Presentation Options

The values of a stereotype that have been applied to a model element can be shown as part of a comment symbol tied to the

model element. The values from a specific stereotype are optionally preceded with the name of the applied stereotype within

a pair of guillemets, which is useful if values of more than one applied stereotype should be shown.

If the extension end is given a name, this name can be used in lieu of the stereotype name within the pair of guillemets when

the stereotype is applied to a model element.

It is possible to attach a specific notation to a stereotype that can be used in lieu of the notation of a model element to

which the stereotype is applied.

It is a semantic variation point that a tool can choose to display or not stereotypes. In particular, some tools can choose

not to display “required stereotypes",?but to display only their attributes (tagged values) if any.

Icon presentation

When a stereotype includes the definition of an icon, this icon can be graphically attached to the model elements extended

by the stereotype. Every model element that has a graphical presentation can have an attached icon. When model elements are

graphically expressed as:

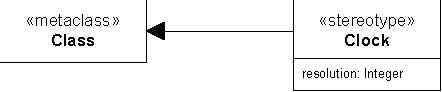

• Boxes (see Figure 13.13 ): the box can be replaced by the icon, and the name of the model element appears below the icon. This presentation option can be used only when a model element is extended by one single stereotype and when properties of the model element (i.e., attributes, operations of a class) are not presented. As another option, the icon can be presented in a reduced shape, inside and on top of the box representing the model element. When several stereotypes are applied, several icons can be presented within the box.

• Links: the icon can be placed close to the link.

• Textual notation: the icon can be presented to the left of the textual notation.

Several icons can be attached to a stereotype. The interpretation of the different attached icons in that case is a semantic

variation point. Some tools may use different images for the icon replacing the box, for the reduced icon inside the box,

for icons within explorers, etc. Depending on the image format, other tools may choose to display one single icon with different

sizes.

Some model elements are already using an icon for their default presentation. A typical example of this is the Actor model

element, which uses the “stickman? icon. In that case, when a model element is extended by a stereotype with an icon, the

stereotype’s icon replaces the default presentation icon within diagrams.

Style Guidelines

The first letter of an applied stereotype should not be capitalized. The values of an applied stereotype are normally not

shown.

Examples

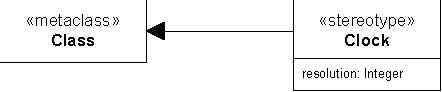

In

Figure 13.12

, a simple stereotype Clock is defined to be applicable at will (dynamically) to instances of the metaclass Class.

Figure 13.12 - Defining a stereotype

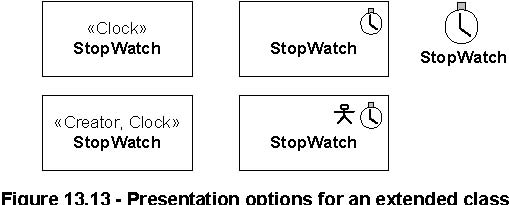

In

Figure 13.14

, an instance specification of the example in Figure 13.12 is shown. Note that the extension must be

composite, and that the derived isRequired? attribute in this case is false. Figure 13.14 shows the repository schema of the

stereotype “clock? defined in Figure 13.12. In this schema, the extended instance (:Class; “name = Class?) is defined in

the UML2.0 (reference metamodel) repository. In a UML modeling tool these extended instances referring to the UML2.0 standard

would typically be in a “read only? form, or presented as proxies to the metaclass being extended.

(It is therefore still at the same meta-level as UML, and does not show the instance model of a model extended by the

stereotype. An example of this is provided in Figure 13.16 and Figure 13.17.) The Semantics sub-section of the Extension

concept explains the MOF equivalent, and how constraints can be attached to stereotypes.

metaclass

ownedAttribute

type

type

extensionownedAttribute

type

ownedEnd, memberEnd

memberEnd

Figure 13.14 - An instance specification when defining a stereotype

In

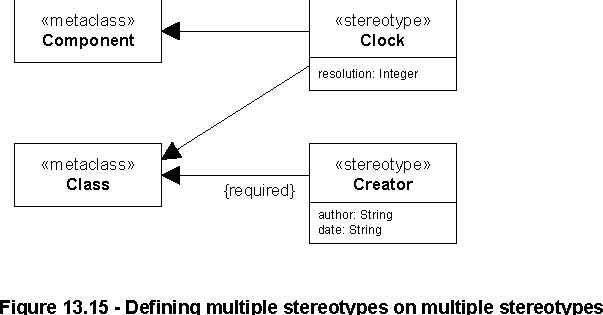

Figure 13.15, it is shown how the same stereotype

Clock can extend either the metaclass Component or the metaclass Class. It is also shown how different stereotypes can extend

the same metaclass.

Figure 13.16

shows how the stereotype Clock

, as defined in Figure 13.15, is applied to a class called

StopWatch.

Figure 13.16 - Using a stereotype

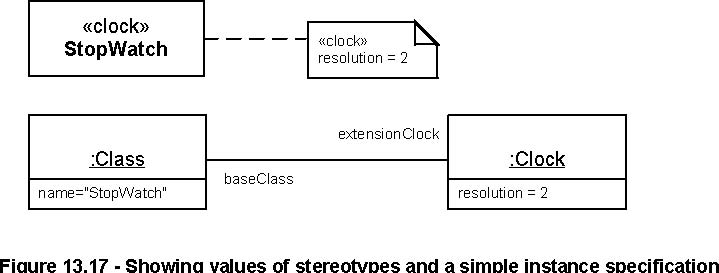

Figure 13.17 shows an example instance model for when the stereotype

Clock is applied to a class called StopWatch. The extension between the stereotype and the metaclass results in a link between

the instance of stereotype Clock and the (user-defined) class StopWatch.

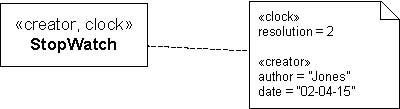

Next, two stereotypes, Clock and Creator

, are applied to the same model element, as is shown in Figure 13.18. Note that

the attribute values of each of the applied stereotypes can be shown in a comment symbol attached to the model element.

«creator, clock»

StopWatch

Figure 13.18 - Using stereotypes and showing values

Changes from UML 1.4

In UML 1.3, tagged values could extend a model element without requiring the presence of a stereotype. In UML 1.4, this capability,

although still supported, was deprecated, to be used only for backward compatibility reasons. In UML 2.0, a tagged value can

only be represented as an attribute defined on a stereotype. Therefore, a model element must be extended by a stereotype in

order to be extended by tagged values. However, the “required? extension mechanism can, in effect, provide the 1.3 capability,

since a tool can in those circumstances automatically define a stereotype to which “unattached? attributes (tagged values)

would be attached.